The Gothic, The Uncanny, and Edward Scissorhands

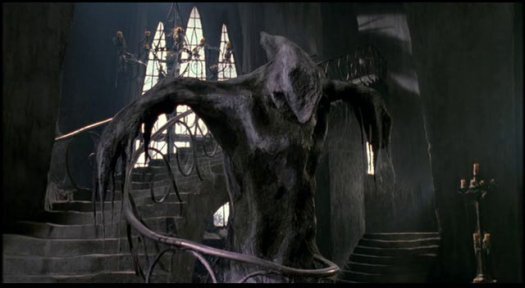

The Gothic Castle, rendered in Tim Burton style. (Edward Scissorhands, 1990)

In Freud’s seminal 1919 essay “The Uncanny,” one idea he repeatedly underscores is that the Uncanny–or, in the German, the unheimlich–is not purely that which is gruesome, even as gruesomeness can contribute to the Uncanny. Instead, the Uncanny is bound up in notions of a rupture to the familiar–something we know well that is twisted in some significant way, exaggerated, shifted, not quite right. The Uncanny is the notion for which Freud perhaps is most often cited–literary theory, art criticism, aesthetics, and even the field of robotics all engage with the concept– and it’s one of his more generative ideas, giving us a name for what is largely an ineffable concept.

It’s also a key element in the work of Tim Burton, whose 1990 film Edward Scissorhands is largely built upon the notion of the Uncanny. In many ways Edward Scissorhands functions as a synchedoche for Burton’s larger body for work, including the wry humor and physical comedy of earlier works like Beetlejuice (1988) and the stylized Gothic fetishism of later films like Sleepy Hollow (1999). Sarah Higley describes the film’s “macabre charm,” arguing that in Edward Scissorhands it is the way Burton highlights “the distinction between normal and abnormal” that gives real meaning to the film (437). In The Coherence of Gothic Conventions, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick describes the Gothic as “an aesthetic based on pleasurable fear” (11); this dichotomy between “normal” and “abnormal” that Higley highlights is tied to the Uncanny, but especially in this film it is deeply bound up with the Gothic.

Sedgwick repeatedly returns to the spatial influence that the Gothic exerts, not only on the physical environment but on the constitution of self. In the Gothic, space is structured as disorienting–it erodes and frustrates boundaries between inside and outside, between interior and exterior, creating confusion and overlap that is expressed both aesthetically and psychologically. It stems from the rupture that results when the self is “massively blocked off from something to which it ought normally to have access” (12). That which is denied varies:

This something can be its own past, the details of its family history; it can be the free air, when the self has been buried alive; it can be a lover; it can be just all the circumambient life, which the self is pinned in death-like sleep. (12)

In Edward Scissorhands, this rupture is expressed both spatially and subconsciously. The dark and brooding hill upon which sits the Inventor’s castle is itself a vertical rupture in the flat landscape of the suburban setting, rendered as a pastel hellscape comprised of strong horizontal sensibility. The castle in which Edward lives (read: hides)–highly influenced by Murnau’s 1922 Nosferatu and the hilltop castle of Count Orlock–is a peculiar space, gray and crumbling, his attic bedroom open to the sky through the decaying roof; however, the space is also punctuated by Edward’s fantastical topiary beasts inside the inner courtyard–a lovely secret from the outside world, much like Edward himself. The town has no sense of history, as if it appeared in its entirety where it sits; the interior spaces are fractured from the exterior spaces, seeming larger than the houses themselves; the decor from house to house has a relentless, stifling sameness to it that both minimizes difference within the film while having the affect of unsettling the audience by offering no real markers with which to orient ourselves. The housewives are all seemingly cut from the same cloth, but there is a terrifying sense of desperation just beneath the surface that erupts in the controlled malestrom of one-upmanship amongst them. They are all cut off from the one thing that would make their existence more bearable: meaning.

For a while, it seems as if Edward–or, rather, the novelty which Edward represents–might be a source for that meaning–the creative touches he brings to this community imbues the neighborhood with a fresh vitality. But in the end, the film’s dedication to both the original shape of fairy tales and to its Gothic structure means that the Uncanny nature of Edward–almost human, but not quite; almost a man, but not quite; almost a productive capitalist, but not quite–requires a metaphoric burial, with Kim’s brandishing of a scissorhand prototype to sate the bloodthirsty mob and Edward’s return to his decaying solitude.

Works Cited

Freud, Sigmund. “The Uncanny.” 1919. https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “The Structure of Gothic Conventions.” The Coherence of Gothic Conventions, Methuen, 1986, pp. 9-36.

Higley, Sarah L. “‘Cunning Work’: Edward Scissorhands and the Topos of Utility.”Christianity and Literature, vol. 42, no. 3, Spring 1993, pp. 434-43.